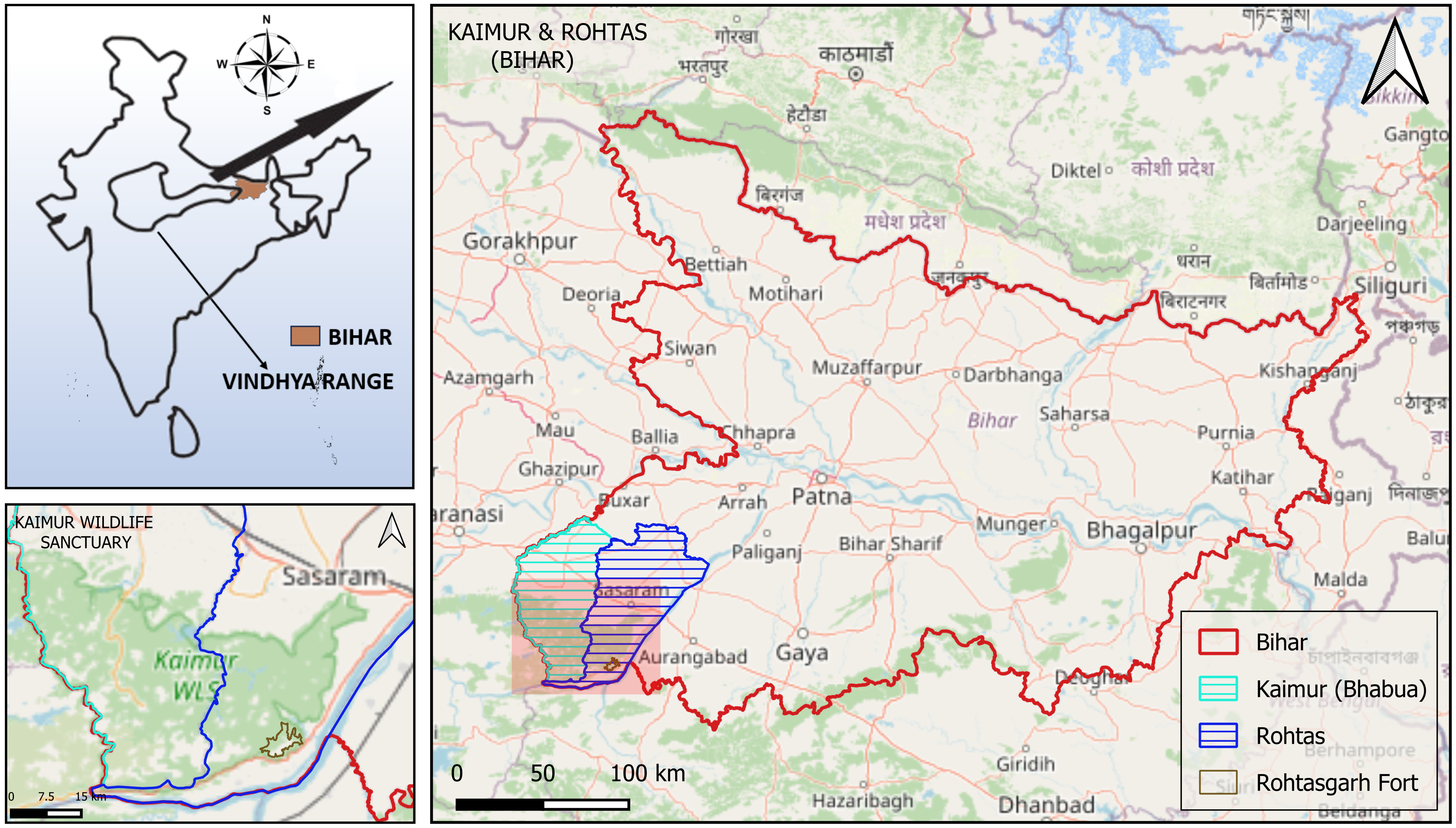

The Kaimur Hills, located at the eastern edge of the Vindhya Mountain range and spanning parts of Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh, form an ecological and cultural corridor rich in biodiversity and ancient heritage sites, including the iconic Rohtasgarh Fort. The region is renowned for its ancient rock art and sacred places that preserve millennia-old traditions. The story of Kaimur cannot be explained by biodiversity data alone.

For generations, the Oraon tribe protected this territory. According to local oral traditions and historical records, the community was displaced in the 16th century when Sher Shah Suri seized Rohtasgarh Fort through deceit. Forced to abandon their homeland, many Oraons were displaced across eastern and central India – but their spiritual connection to Rohtasgarh never faded.

Since 2006, the Rohtasgarh Mahotsav – also known as the Vanvasi Kalyan Mahotsav – has welcomed thousands of Oraon, Kharwar, and other Vanvasi community members back to their ancestral land during Magha Purnima. These community members perform rituals at the Karam tree before taking sacred earth from its base to use in their household shrines.

The act holds deep spiritual meaning because it represents their duty to protect the land. Through their hands, soil transforms into memory, while worship becomes a system of accountability. Their traditional protection system is rooted in inherited responsibility rather than policy-based mechanisms.

These rituals – documented through oral histories and spatial mapping – reveal a form of emotional conservation: a deeply rooted sense of stewardship tied not to regulations, but to memory, reverence, and ancestral duty. Although I am not from the Oraon community, I was born and raised in Bihar’s Kaimur district, which, along with Rohtas district, forms part of the region where the Kaimur Hills stretch and the historic Rohtasgarh Fort is located.

Over the years, I noticed that despite the region’s immense historical, cultural, and ecological value, it has received little attention compared to other heritage sites in India, which inspired me to focus my work on documenting my state’s heritage. My research began with Rohtasgarh Fort, which led me deeper into the area’s history and its strong association with the Oraon community.

With a background in archaeology and heritage management, professional experience with ASI, IGNCA, and NIAS, and as a Member of the IUCN Commission on Education and Communication (CEC), I focus on communicating community-linked conservation stories. This approach echoes the IUCN World Conservation Congress theme of Delivering on Equity. The terrain of Kaimur also supports sustainable ecotourism development.

The sacred nature of Tutla Bhavani, Telhar Kund and the Rohtas plateau provide deep immersive experiences for visitors. A nature-positive economy grounded in cultural continuity could thrive here - through community-led heritage walks, forest-based homestays and tribal craft initiatives (UNEP 2021) that support sustainable livelihoods.

Ultimately, the return of the Oraon people is not just a cultural festival - it’s a blueprint. It shows that when we link natural heritage to cultural memory, a new kind of conservation emerges: one sustained not only by law but by love. Today, we are called to walk with the original guardians of this land, to protect what they never forgot.

As I prepare to share Kaimur’s story at the IUCN World Conservation Congress 2025, I carry with me this belief: that cultural memory and emotional accountability must sit alongside science and policy. Attending remotely, I will engage in virtual sessions, participate in thematic discussions, and share this story in relevant knowledge-sharing spaces and through IUCN platforms and groups. I also aim to learn from global experts, ask questions related to my work, and build connections with delegates, Indigenous leaders, and specialists that can support future documentation and conservation work in Kaimur and Rohtas.

Ultimately, my broader aim is to present Kaimur Hill as an interconnected natural–cultural heritage site with potential for UNESCO recognition. This is the future of transformative conservation – one that delivers on equity, embraces Indigenous leadership, and nurtures economies rooted in reverence and resilience.